Can Agile Governance Restore Trust in Government ?

The social unrest Latin America is going through reflects the frustrated aspirations of a growing, but vulnerable middle-class that expects better public services and greater social justice. For this to happen, bureaucracies need to put people first.

"Bureaucracy is the art of turning the easy into the difficult by means of the useless" Carlos Castillo Peraza, Mexican intellectual and politician (1947-2000)

The Age of Unmet Expectations

"It’s not for 30 pesos, it’s for 30 years." The violent protests in the streets of Santiago de Chile reflect the discontent of citizens in many countries in the region who have not seen their lives improve.[1] In the Chilean case, the 30- pesos increase in the subway tariff was the ‘straw that broke the camel’s back’. Protesters say they feel abused and forgotten by an unfair economic model, in which the cost of living continues to rise while citizens’ aspirations are frustrated in a context of political disaffection.[2] Trust in the system is undermined by an ‘incestuous relationship’ between the political and economic elite. People’s expectations have grown faster than their incomes. Urban "digital natives" have come to aspire to better lives and tolerate less corruption at a time when new generations tend to be worse off than their parents. These trends reinforce deep-seated inequalities in incomes, access and opportunities. As summed up recently, "Chile is a country with the income level of a rich one and the inequality of a poor one."[3] Meanwhile, across the region, "economic hardship has focused protesters’ anger on related issues such as inequality and corruption. Latin America has long been one of the world’s most unequal regions, but the limits of what people consider tolerable are shifting."[4]

Public services in the most unequal region in the world provide less and less protection to citizens, generating growing precariousness.[5] The social malaise in Latin America reflects the frustrated aspirations of a growing but vulnerable middle class that expects better public services from its governments and greater integrity from its politicians. However, "the international enthusiasm over the growth of the middle class was based on income metrics without regard to the degree of access to formal jobs or services, or the presence of a social safety net."[6] This development model is "à bout de souffle" and must change course. Despite important social progress and poverty reduction, it has failed to meet citizens’ expectations for a better life, and in turn, damaged citizens’ trust in politicians.

A Region Addicted to Regulation

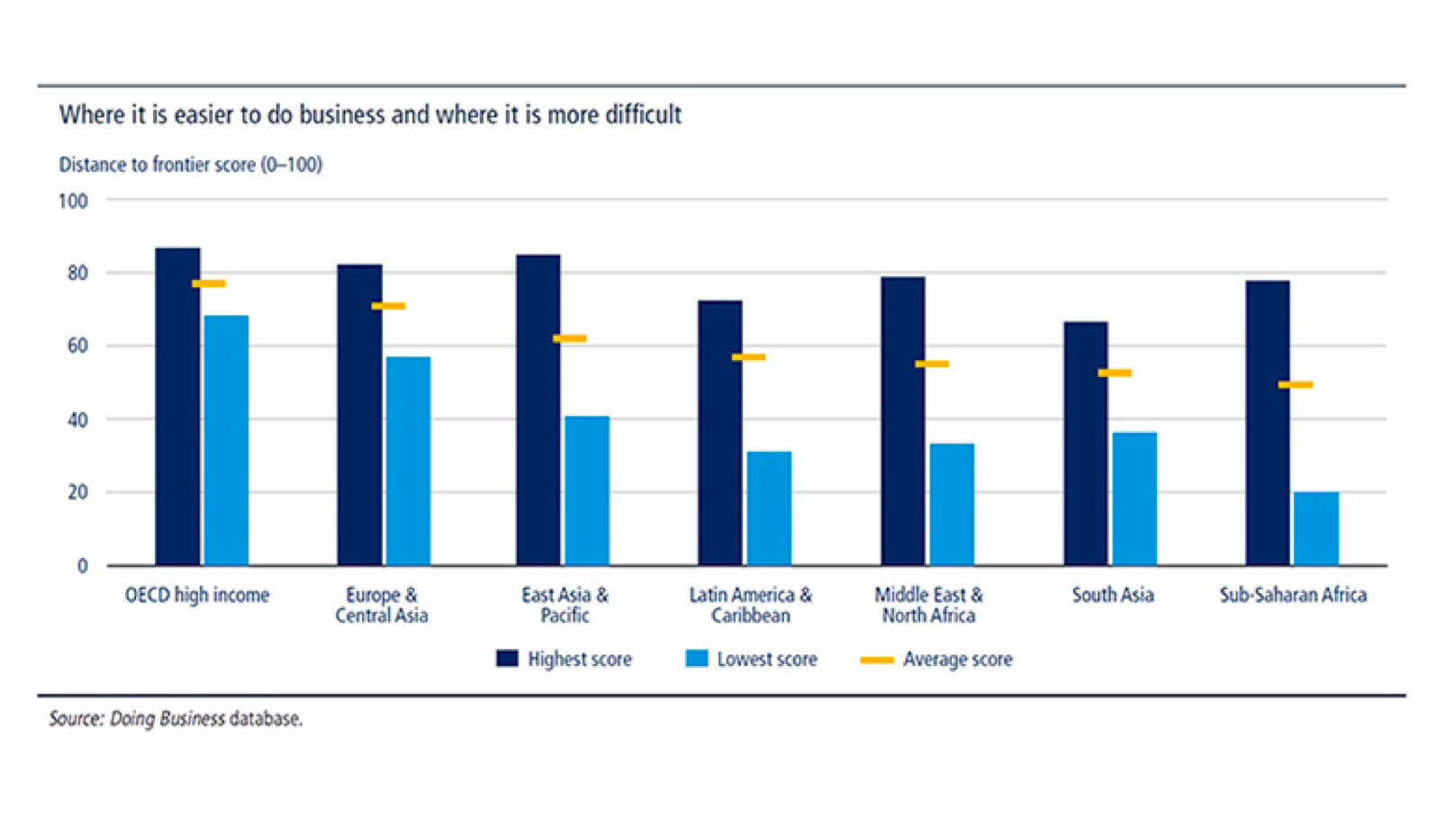

Latin America lags behind other regions of the world in providing an enabling environment for doing business, a major obstacle for its productivity and competitiveness. The burden of regulations and the prevalence of red tape undermine the social contract between the state and citizens. They weaken the productivity of small firms, which make up the bulk of the region’s industrial fabric. According to the 2020 World Bank report on the business climate,[7] the region stands out for the asphyxiating burden of its regulations, reflected in the number and complexity of its bureaucratic procedures. The region’s performance is not dissimilar to that of the Middle East and North Africa, notwithstanding the difference between countries within those regions.

Graph 1: Ease of doing business across regions (WB DB 2018)

Source: World Bank, Doing Business 2018

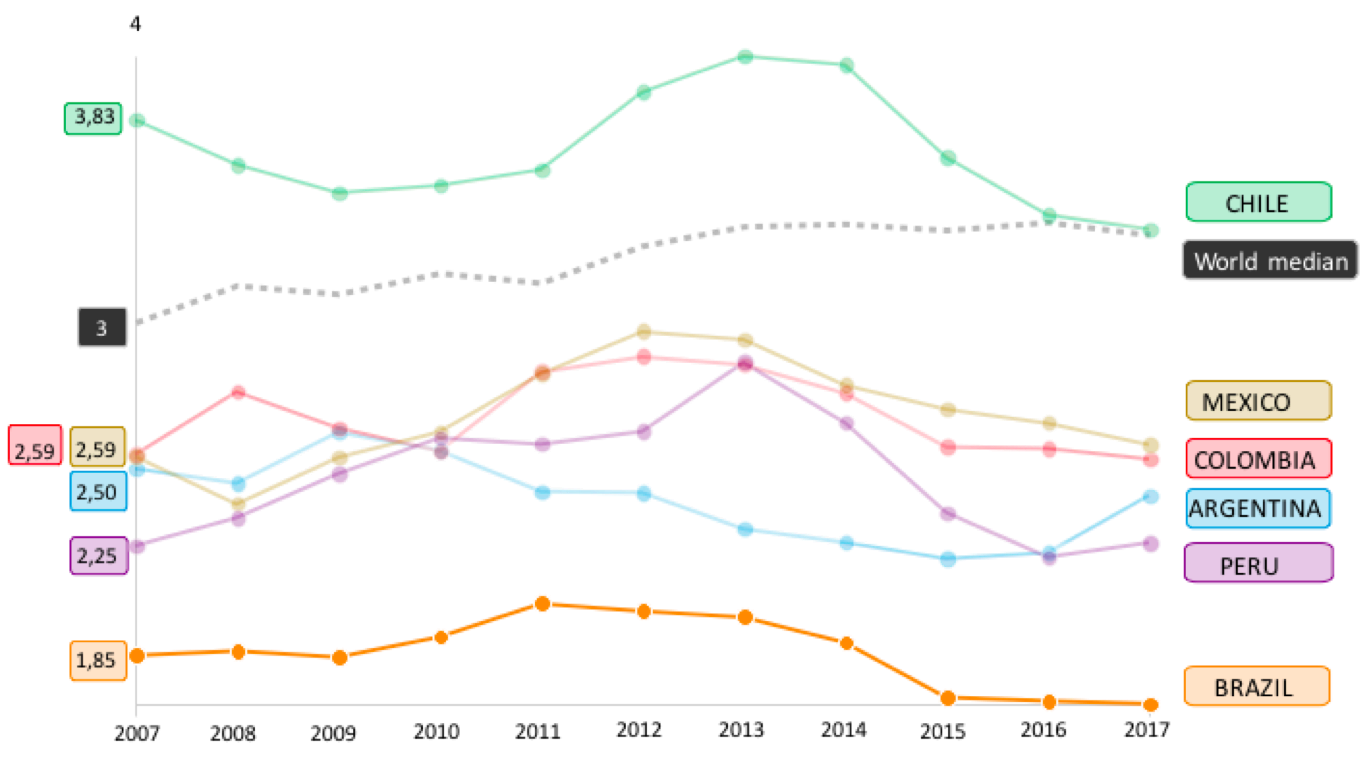

No country in the region is among the 50 most agile in the world, with Chile in 59th place and Mexico in 60th place out of 190 countries assessed by the World Bank. In Brazil, famous for its "custo Brasil"[8], a medium-sized busin ess must spend 1,500 hours per year to meet its tax obligations, compared to 159 hours, almost 10 times less, in OECD economies. In Colombia, in order to enforce a court ruling, a company spends three years on average, and the costs involved amount to 46% of the litigation, more than twice as much as the OECD’s average. The World Economic Forum’s index assessing the burden of government regulation reaches the same conclusions, reflecting the region’s worsening performance in recent years.

Graph 2: The burden of government regulation (scale 1-7 best)

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Report (Geneva: World economic Forum, 2019), extracted from World Bank’s TCdata360[9]

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Report (Geneva: World economic Forum, 2019), extracted from World Bank’s TCdata360[9]

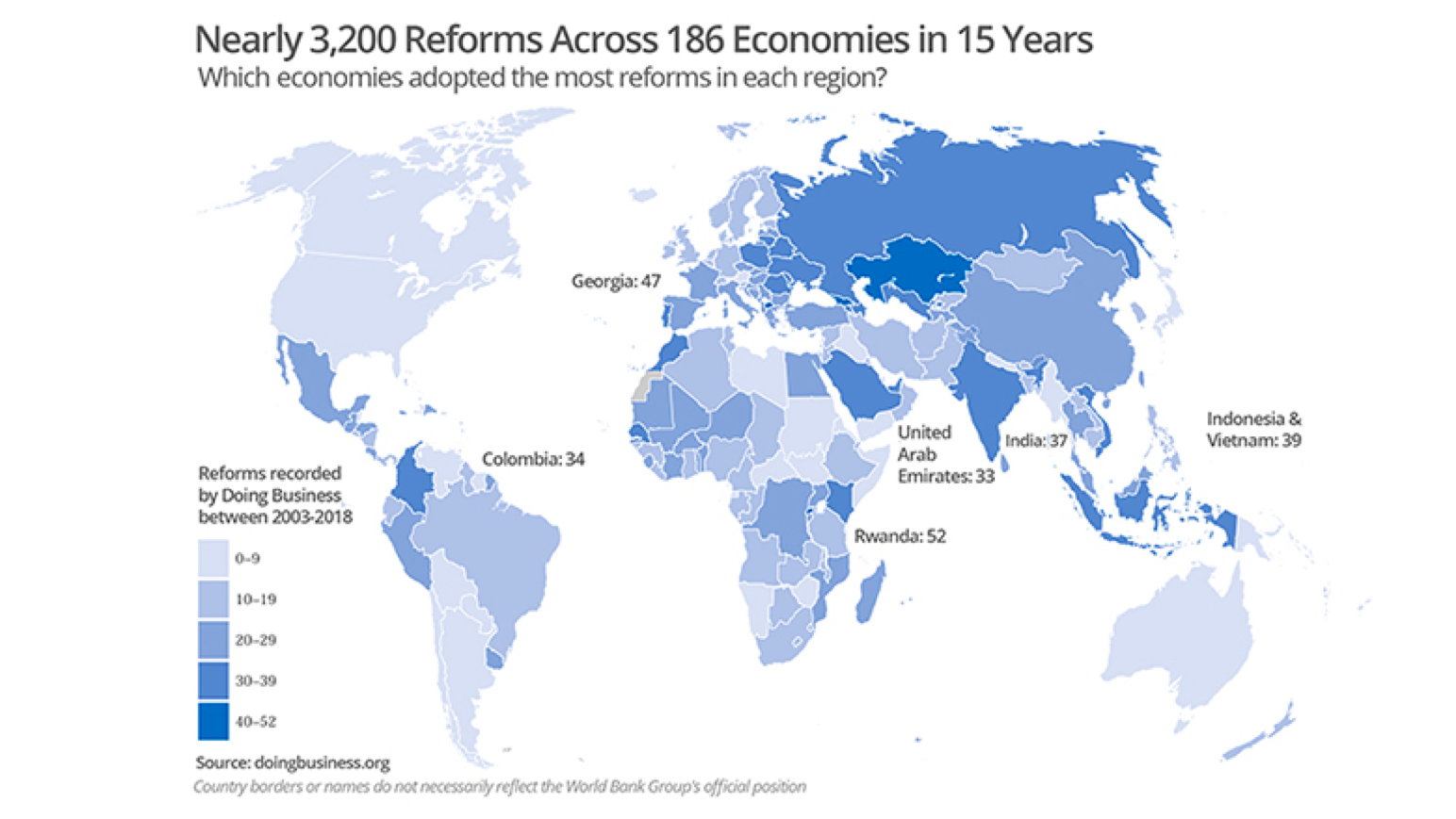

At the same time, the region stands out in its efforts to cure itself. Last year, 21 of the region’s 32 economies carried out 35 regulatory simplification reforms. Colombia stands out with 37 reforms since 2005, with 3 major reforms in the last year to facilitate the creation of companies. In the 15-year period 2003-2018, it introduced 34 major reforms, a reform activity similar to that of the United Arab Emirates.[10] Argentina introduced an aggressive productive simplification program that accelerated the issuance of construction permits through an electronic platform and facilitated the fulfillment of contracts by introducing electronic payment for judicial procedures.

Graph 3: Regulatory reforms around the world between 2003 and 2018

Source: World Bank, Doing Business 2018; graph extracted from here.

Source: World Bank, Doing Business 2018; graph extracted from here.

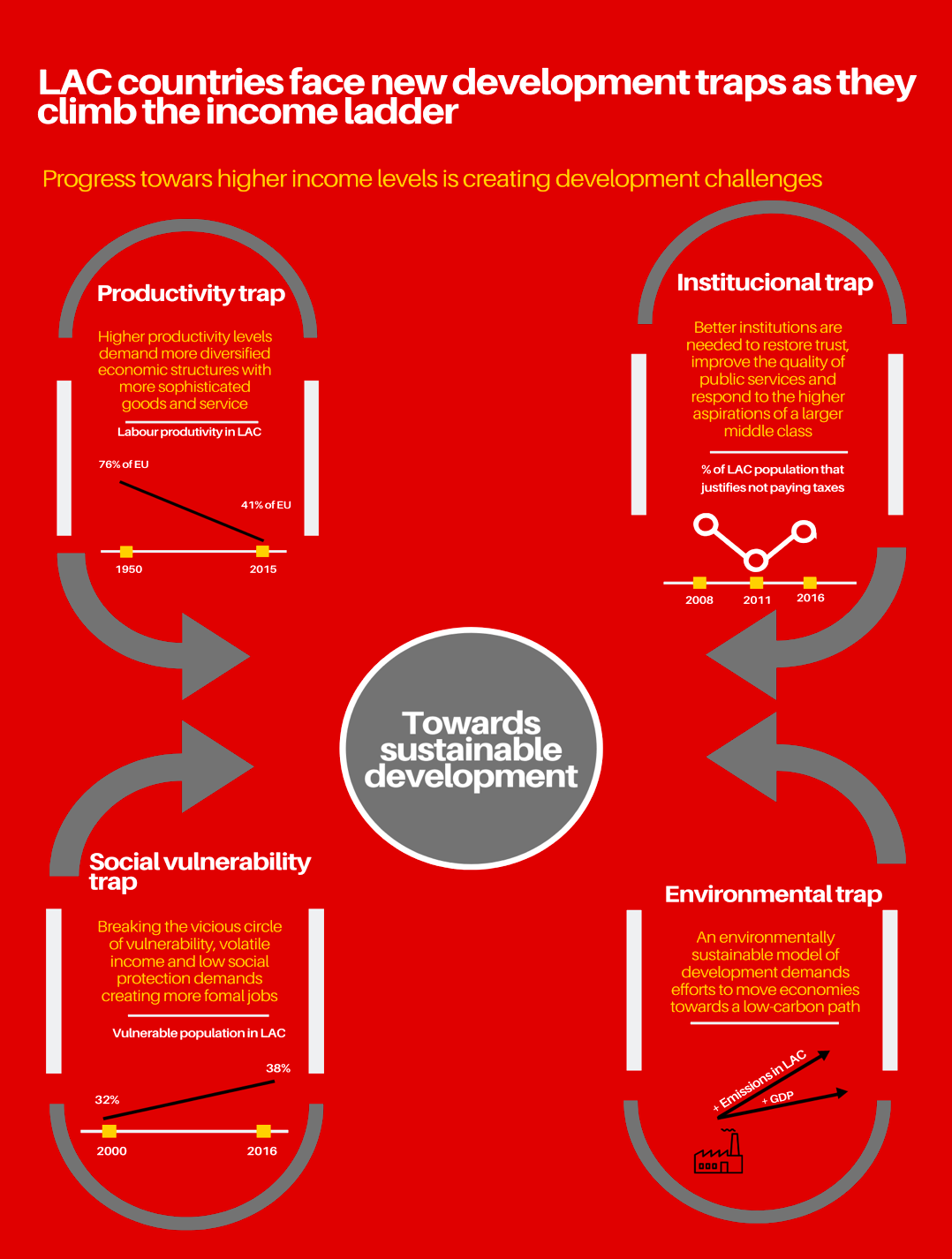

In a region with a critical need to mobilize public resources to finance more equitable development through fairer taxes, tax morale is strikingly low. According to the World Bank, South America is the region of the world where paying taxes is most complex and expensive.[11] In addition to a large informal economy, the region suffers from aggressive tax avoidance and sophisticated tax evasion, including through particularly creative tax exemptions. According to the OECD,[12] in 2015, 52% of Latin Americans considered it justified to evade taxes. A lack of trust in the state reduces tax collection and, in turn, low tax collection exacerbates institutional weakness and diminishes the capacity of states to provide services. The region, mainly comprised of middle-income countries, is caught in multiple developmental "traps", including what the OECD describes as an "institutional trap".[13] An important lesson for the Arab world from Latin America’s experience is that emerging economies "face new development traps as they climb the income ladder." Recent social protests are fueled, in part, by social injustice and a broken social contract which has failed to share wealth and guarantee social welfare. The tax system fails to act as a mechanism to promote greater equity and ensure solidarity, explaining why inequality, as measured by the Gini-coefficient, remains almost unaltered after taxes and transfers.

Graph 4: Development traps in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC)

Source: Adapted from OECD-CAF-CEPAL. Latin American Economic Outlook 2019: Development in Transition (Paris: OECD).

The bureaucratic jungle of the region’s states remains its main Achilles’ heel. The paradox is that Latin America is the region with the most rules and, at the same time, the region that respects them the least. The complexity of administrative procedures and the discretion of the public officials who handle them make them particularly vulnerable to bribery. The countries with the most regulations tend to be the most corrupt as well. According to a recent report by CAF, Development Bank of Latin America, on Integrity in Public Policies,[14] one in four Latin Americans declares having paid a bribe to receive a service or expedite a procedure.

How to Advance "Agile Governance" Under these Conditions?

Rather than ad hoc reforms, what the region needs is a shock therapy that addresses both the large stock and the incessant flow of new regulations. The frustrations of Latin Americans protesting in the streets are directed against their tangled and old-fashioned bureaucracies in the era of the fourth industrial revolution. The legalistic culture of the administrations makes them think that every public problem can be solved through a norm. The response to the recurrent corruption scandals is reinforcing this regulatory pathology, with lawmakers generating even more norms and controls. However, institutional informality creates an abysmal gap between formal rules and informal practices. Formal rules are manipulated rather than respected. The digital transformation of the state apparatus offers an opportunity to transition towards smarter regulation and greater innovation in government, what the World Economic Forum labels "agile governance."[15] This requires a change in the legalistic culture of the bureaucracy, putting citizens at the center and reengineering processes from their perspective.

Faced with this situation, governments in the region are seeking to "de-bureaucratize" the state, that is streamline bureaucracies, reduce red-tape and mainstream innovation.[16] In Brazil, "de-bureaucratization" is a central mandate of the all-powerful economy ministry. In Ecuador, the government has begun an ambitious program of regulatory reform, with a law in 2018 to streamline administrative procedures.[17] Meanwhile, Argentina made important advances in the digital transformation of the state, and Chile moved forward with a plan to achieve a state "without paperwork and without queues" with the approval of the law of digital transformation of the state.[18]

One of the main strategies to make government simpler is to digitize services and streamline procedures. Brazil has recently launched its single portal for digital services (www.brazil.gov.br) and Colombia (www.gov.co) will consolidate its own for 2020, following in the footsteps of Mexico (www.gob.mx) and Peru (www.gob.pe) and modelled after the United Kingdom with the pioneering www.gov.uk. In Uruguay, 68% of national government procedures can now be started and completed online.[19] In Chile, the announced goal is that 80% of procedures will be digitalized by the end of the current government. However, in order to move forward with this structural transformation, it is key to modernize the crosscutting enablers that provide the foundation upon which to build digital government and digital services. These enablers include in particular a single digital identity, interoperability between data platforms, and digital payment systems.

It is not surprising that tax agencies have been at the forefront of the digital transformation in many countries. Digital solutions help increase the efficiency of tax collection and reduce tax fraud. They are also contributing to increase voluntary compliance by making it easier for taxpayers to fulfil their obligations. For example, several countries have introduced pre-filled tax returns and online payment systems. The digitalization of tax processes, the proliferation of bi g data and the expansion of social networking technologies also enable tax authorities’ oversight capabilities through the deployment of data mining and fraud analytics solutions. In France and Spain, tax administrations already use artificial intelligence to detect tax fraud and tax evasion. Thanks to the use of data mining, the collection of tax debts increased by 40% in the first half of 2019.[20]

However, digitalizing is not enough; governments must simplify. If an administrative procedure is incoherent, inadequate or simply obsolete, it will remain so even when digitalized. That is why another set of reforms focuses on streamlining administrative processes and reconsidering the rationale of existing regulations, through the ex-ante evaluation of their impact and the ex-post review of their relevance. This requires rethinking bureaucratic procedures as "digital by default", reviewing their justification and cutting requirements, many of which are outdated in the digital age. There are many simplification strategies, from the most radical regulatory "guillotine" through which regulations are extinguished if not reconfirmed by certain time, as in Peru, to narrower strategies of "regulatory cleansing" and ex-post reviews.

Colombia, for example, adopted a roadmap to rationalize the regulatory production in 2014 to deal with the flow of new regulations. According to the government’s own estimate, Colombia, which ranks 123 out of 141 in the World Economic Forum’s indicator of regulatory burden, issued almost 30 regulations per day between 2010 and 2016, totaling 95000 new laws, rules and regulations. It thus still needs regular "regulatory clean-up" initiatives such as Simple State, Colombia Agile[21] which in the first year of the current government have rationalized more than a thousand rules and procedures.[22] Another group of reforms focuses on efforts to reform regulatory policies and governance. Such reforms tend to require longer maturation as well as greater political capital to enact and implement them. Mexico culminated two decades of reforms in 2018 with the adoption of the federal law on smarter regulation, after two decades of discussions and negotiations. It created in 2000 a federal entity in charge of regulatory governance and driving regulatory reform, at both the federal and state levels.

A critical lesson for the Arab world from this experience is that it is futile to rationalize an existing stock of regulations if one does not tackle its root cause in the flux of new regulations.

What Can Arab Countries Learn from Latin America?

Many Arab countries face numerous governance challenges which are not so different from those facing Latin American governments. There are three important lessons that the Arab world can draw from Latin America’s ongoing experiences in pursuing more agile systems of governance in the face of developmental challenges and complexities.

A first lesson is that modern bureaucracies must conceive regulation policy as a core function of government. This entails clear and predictable rules that can be expected to be enforced fairly and uniformly. Governing regulatory policy is best done from the center of government (typically the ministry of the presidency or cabinet of the prime minister), as a crosscutting function that requires strong political backing and "tone from the top" to align regulatory practices of sector ministries. Smart government requires smart regulation. This entails disciplining the production of rules and regulations in large bureaucracies and autonomous bodies that often regulate in isolation. A major challenge for emerging economies is rationalizing regulations across the entire public sector, and across sectors and levels of government. For this to happen, reformers need to address the root cause of over-regulation. Too often, reformers focus on the stock of existing regulations, rather than disciplining the flux of new regulations. While digitalization will make existing regulations less cumbersome by automating processes, it will not discipline the production of new regulations. However, as recent reforms in Argentina suggest, automating processes and records can help governments understand bottlenecks better because they generate new data insights on the functioning of bureaucracy. In designing bureaucratic procedures as "digital by default", governments not only need to rethink them from the user’s perspective but also generate more and better information about their actual functioning.

A second lesson is that agile governance requires greater coordination between digital transformation, administrative simplification, and regulatory governance. These core government functions are often pursued by different entities whose incentives are not always aligned. This arrangement is untenable in the age of digital disruption. The challenge is dual in nature. It requires coordinating multiple agencies at the center of government to govern regulatory policy, while streamlining regulatory practices across government with large sprawling bureaucracies, many autonomous entities, state-owned enterprises and subnational governments. In other words, smart regulation requires a strong strategic center able to enforce whole-of-government approaches. Fast-paced digital transformation is forcing central agencies to change to adjust to the evolving nature of the digital economy. On the one hand, they can now leverage new technologies and data insights to perform their functions better. On the other hand, they must regulate the use of new technologies and big data in the new economy. Regulating the governance of data in the new economy is probably the greatest challenge they face, in particular in relation to the governance of data and the use of artificial intelligence. For emerging economies in the Arab world and Latin America, the challenge is to remain relevant in the global digital economy and have a say in its regulation.

A fundamental lesson of the social malaise in Latin America is that simplifying government and making it more agile is not enough. Government’s digital transformation is certainly part of the solution on the path towards better regulation and smarter governments that leverage new technologies and data insights to improve the design and delivery of public services. Ultimately, however, governments need to improve the quality of public services and reduce social inequalities in the context of more equitable development.

End Notes:

[1] Patricio Nava, "Chile’s Riots: Frustration at the Gate of the Promised Land," Americas Quarterly, 21 October 2019.

[2] Rocio Montes, "Claves de las protestas en Chile: La olla a presión revienta en el oasis," El País, 21 October 2019.

[3] Jorge Galingo, "Los datos para entender major por qué estalló Chile," El País, 26 October 2019.

[4] Moises Naím and Brian Winter, "Why Latin America Was Primed to Explode," Foreign Affairs, 29 October 2019.

[5] Javier Lafuente, "La desigualdad moviliza a América Latina," El País, 27 October 2019.

[6] Christopher Sabatini and Anar Bata, "Latin America’s Protests Are Likely to Fail," Foreign Policy, 8 November 2019.

[7] World Bank, Doing Business 2020, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2019.

[8] "Custo Brasil" (or "Brazil cost") refers to the high operational costs associated with doing business in Brazil, making Brazilian goods and services more expensive compared to other countries.

[9] Database available at https://tcdata360.worldbank.org/indicators/govt.regu?country=BRA&indicator=689&viz=line_chart&years=2007,2017

[10] World Bank, Doing Business 2018, Washington DC: World Bank 2018. The Middle East and North Africa is one of the strongest regions in implementing business-facilitating reforms in recent years. Economies of the Gulf region were particularly active, carrying out 35 reforms last year. Four economies in the region are among the 10 most improved globally.

[11] World Bank and PWC, Paying Taxes 2019, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018.

[12] OECD-CAF-ECLAC, Latin American Economic Outlook 2018: Rethinking Institutions for Development, Paris: OECD, 2018.

[13] OECD-CAF-ECLAC, Latin American Economic Outlook 2019: Development in Transitions, Paris: OECD, 2019.

[14] CAF, Integrity in Public Policies, Bogotá: CAF, 2019.

[15] World Economic Forum, Agile Governance: Reimagining Policy-making in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2018.

[16] Carlos Santiso, "América Latina comienza a destrabar la burocracia," El País, 3 February 2017.

[17] See: https://www.gobiernoelectronico.gob.ec/ano-2018/

[18] See: https://www.gob.cl/noticias/presidente-pinera-presenta-la-agenda-de-modernizacion-del-estado-es-hacerles-la-vida-mas-facil-las-personas/

[19] See: https://www.gub.uy/agencia-gobierno-electronico-sociedad-informacion-conocimiento/comunicacion/noticias/tramites-linea-supero-meta-prevista-para-2018

[20] See: https://www.lefigaro.fr/conjoncture/fraude-fiscale-640-millions-d-euros-recuperes-grace-au-data-mining-20191023

[21] http://www.colombiaagil.gov.co/

[22] See: http://www.colombiaagil.gov.co/noticias/estado-simple-colombia-agil-supera-la-meta-del-201

Read more at: https://dubaipolicyreview.ae/can-agile-governance-restore-trust-in-government-lessons-from-latin-america/