The Dos and Don’ts of Urban Innovation

With rapid urbanisation leading more people to live in cities, it’s vital for governments to be ahead of the game in urban innovation. But what constitutes good urban innovation? What are the dos and don’ts?

“Cities are often places of great energy and optimism,” write the authors of the “Future of Cities” report. “They are where most of us choose to live, work and interact with others. As a result, cities are where innovation happens, where ideas are formed from which economic growth largely stems.”

Given their closeness to people, their manageable scale and agility, cities are able to stimulate innovation and transform much more rapidly.

But driving change is not easy, and faced with new and complex challenges and increasing pressure to find solutions to satisfy citizens, city governments are taking new approaches to innovation.

But what constitutes good urban innovation? And what are the key principles or methods that governments should consider to ensure successful transformation efforts?

Here are the Dos and Don’ts.

DO: Place citizens at the heart of the process

City governments have a far better chance at driving change when citizens are at the heart of the process, according to experts at Cities Today Institute, who describe society as “a vital ingredient for successful innovation and adoption of innovative solutions”.

While most urban innovation strategies and initiatives are tech-centric affairs, there is a growing focus on involving the community – the constituents and citizens – with technology now seen as “the easy part”.

There are many benefits to be gained by a taking a citizen-centric approach to urban development. According to McKinsey’s report, “Smart Cities: Digital Solutions for a More Livable Future”, involving citizens can lead to substantial intangible benefits, such as crowdsourcing better decisions and making people feel that their voices are being heard. Two-way communication not only gives city governments a better understanding of their residents’ key concerns, it also draws everyday people into the policy-making process.

There are countless examples around the world that demonstrate how cities are achieving success by consulting with citizens. Better Reykjavík is one example. The online consultation forum in the Icelandic capital gives citizens the chance to present their ideas on issues regarding services and operations of the City of Reykjavík, which has led to many citizen-contributed ideas becoming law.

A similar process in Seoul enables citizens to contribute opinions and ideas on proposed municipal policies through the mVoting mobile app, which provides a platform to millions of voices.

Dubai has initiated a number of urban projects and initiatives through Smart Majlis, which encourages citizens – and even tourists and foreigners – to submit their ideas and feedback on the development of the city.

In Paris, the city’s participatory budget invites citizens to post proposals and vote on which should be funded. This has led to a number of urban improvements, such as a €1.5 million plan to upgrade cleaning facilities, which won more than 37,000 votes in 2018.

Similar participatory budget schemes are underway in cities around the world, including Milan, Glasgow and Madrid.

DON’T: Put citizens' personal data at risk

Artificial intelligence-powered smart city technology is making it easier for cities to innovate and improve public services, and operate in a way that improves everyday life for residents. However, even the most sophisticated systems and organisations can suffer a security lapse.

In Australia, a ransomware attack on state hospital computer networks forced hospitals to isolate and disconnect patient records and booking and management systems, causing widespread disruption.

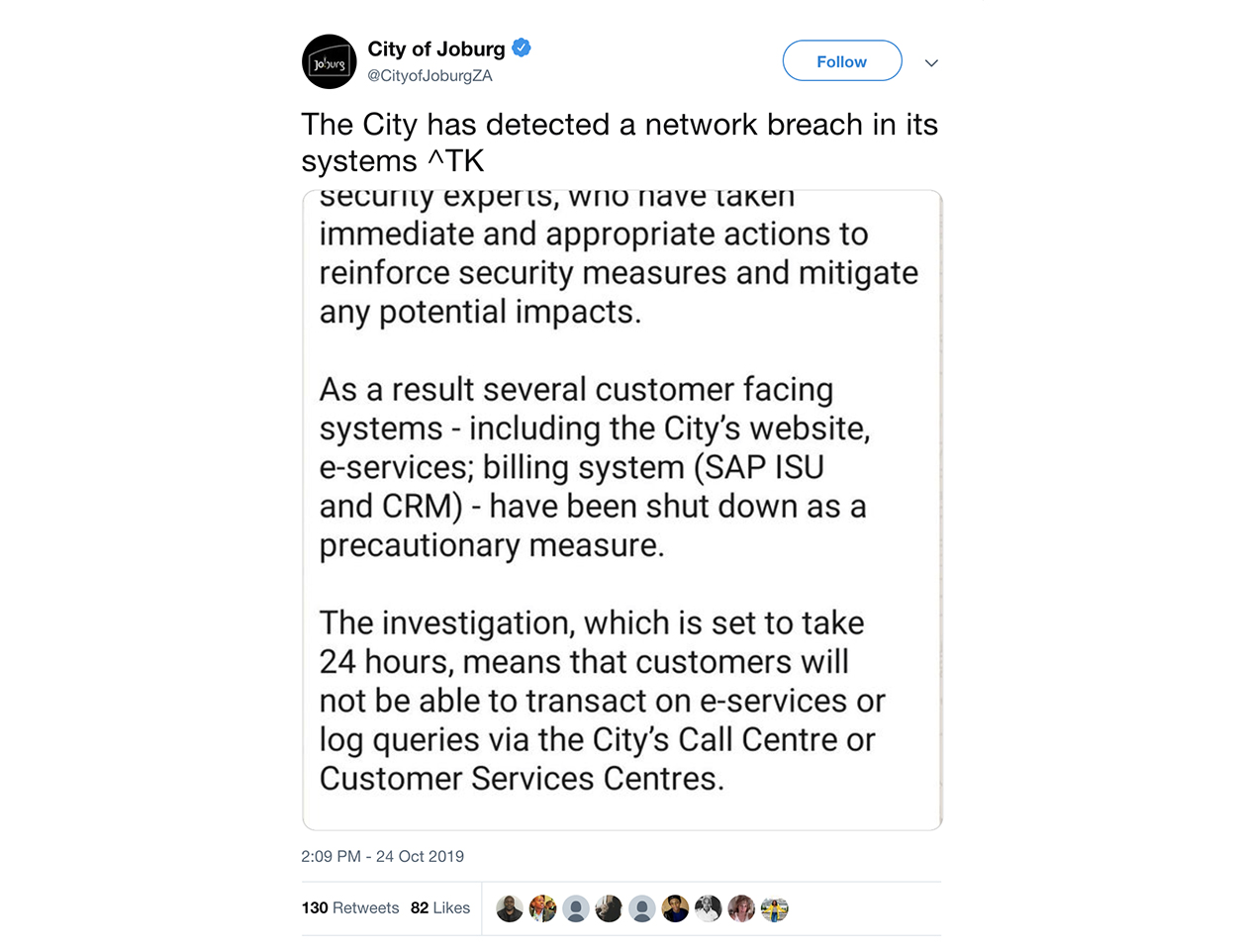

In South Africa, the City of Johannesburg’s computer network was held for ransom by a hacker group, which threatened to publish all personal data online. The breach brought Johannesburg to a standstill with authorities shutting down all IT infrastructure such as websites, payment portals and e-services.

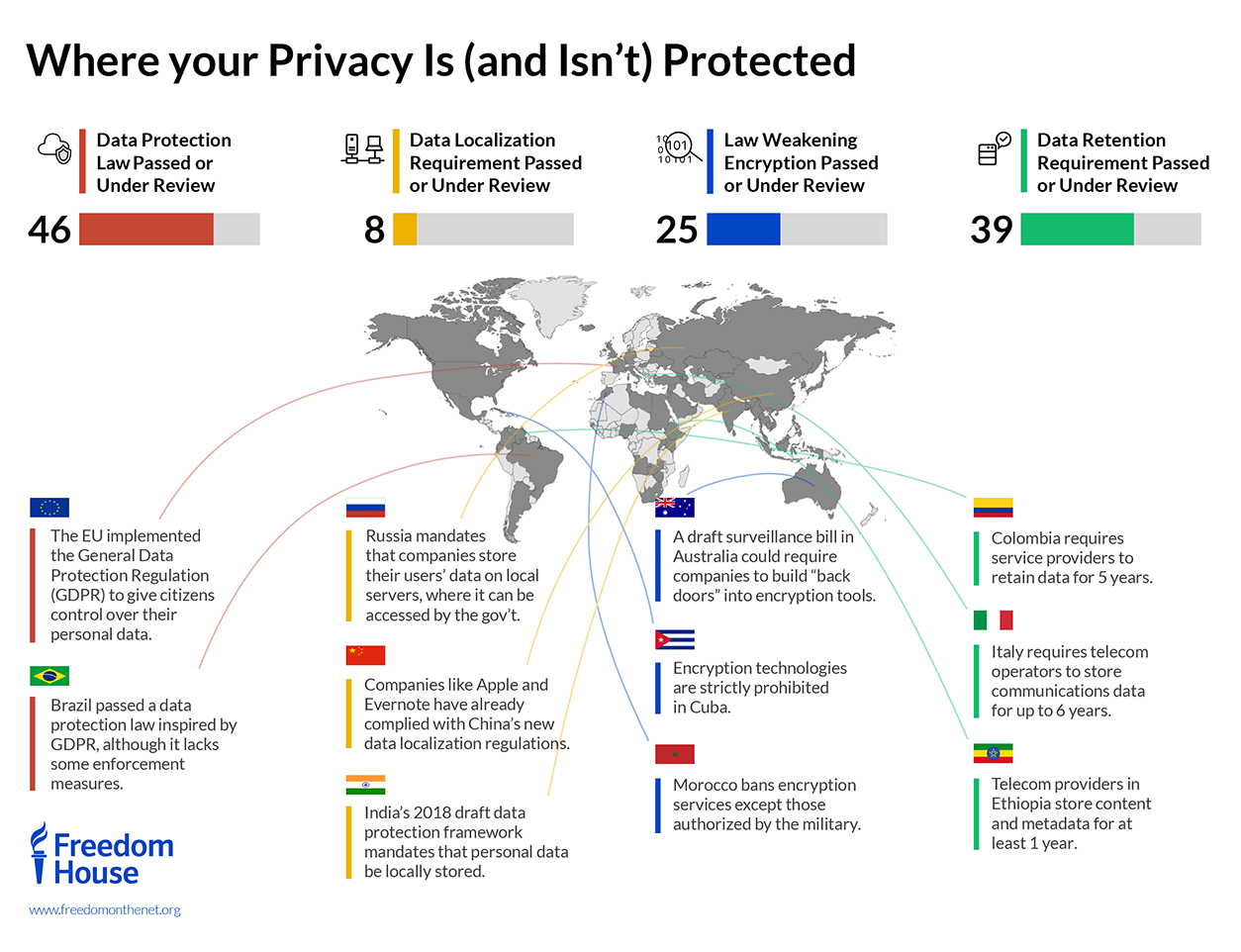

With cyberattacks in the US increasingly targeting vulnerable organisations like local governments and hospitals, and facial recognition and surveillance coming under scrutiny from civil liberties advocates, the pressure on governments to protect the privacy of citizens is mounting.

DO: Define a Massive Transformative Purpose (MTP)

Massive Transformative Purpose (MTP) is defined as one of the seven principles that underpin transformative urban innovation, according to Volans, an innovation and sustainability think tank and advisory firm.

The term, coined in the 2014 book Exponential Organizations, is more than an inspiring mission statement – it’s a catchy, aspirational tagline that sets a purpose.

The idea behind setting a transformative purpose is to inspire greater creativity, which is a known driver of successful urban innovation, and to motivate people and generate action. This can be especially important for city initiatives, which often pull both people and resources from different sectors.

Dubai's Smart Dubai 2021 plan is an example of a Massive Transformative Purpose that led to positive action.

His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum’s vision of a large scale, system-wide, multi-actor transformational effort to make Dubai “the happiest city on earth” led to the implementation of happiness meters deployed at bricks-and-mortar customer centres in the city as well as on online platforms. The meters ask citizens to rate whether they feel happy, neutral or unhappy about their experience, whether at airport immigration, a government service centre, public park, a shopping mall or while using public transport. The data enables the city to continuously review and improve levels of service, and opens new and valuable data for entities in the public and private sector to improve the happiness of their customers and employees.

DO: Champion the use of open data

Cities that open up their data are stimulating change and driving new value creation opportunities.

London’s DataStore is one example of an Open Data platform resulting in urban innovation.

The DataStore contains a range of urban data on everything from property prices to transportation patterns. More than 400 smartphone apps, including Citymapper, have been created based on London’s transport data alone.The Barcelona Open Data portal is another enabling more transparency regarding city services, and showcasing open data based citizen projects within its "Reuser" area.

Paris is also championing the sharing of open data. In a partnership with Bloomberg Associates, which has assisted Paris in building out its modular, open-source Lutece platform, cities around the world are encouraged to download and freely relicense, repurpose and customise already existing software that can help to improve their city operations, rather than recreating costly technology solutions piece by piece.

Offering open data in this way promotes the spirit of collaboration, creating a “universal toolkit” for larger change.

DO: Streamline procurement

According to the Centre for Public Impact “Future of Cities” report, current procurement processes require cities to be prescriptive when requesting vendor proposals, which discourages new vendors from applying – even though they may have more effective solutions to the problem at hand. The traditional city procurement process is also “slow and cumbersome with narrowly defined problems to solve and, too often, a focus on obtaining solutions at the lowest possible cost”.

A frequent frustration for bidders is that governments rarely find ways to centralise qualification information about suppliers, meaning they are repeatedly asked for the same information when pitching across multiple contracts.

Streamlining processes, modelling government procurement after private-sector procurement, and removing some of the bureaucracy and obstacles that discourage suppliers from bidding are all methods that can foster a new culture of procurement – meaning citizens get the services they need faster.

The Welsh Government’s efforts to standardise the pre-qualification stages of procurement led to “SQuID”, the Supplier Qualification Information Database that asks bidders a uniform set of selection-stage questions.

The FastFWD initiative in the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania is another example that streamlined the procurement process for pilot projects. The initiative more than halved the amount of paperwork required for a typical Request for Proposal. The city also opened procurement to a wider pool of applicants by posting in startup forums. In one case, this led to 137 companies from around the world submitting responses.

With outdated legacy procurement systems and business processes, tracking and managing spending is another challenge for governments. An eProcurement system being implemented in the State of Oregon is set to transform the process for state agencies and boost bid participation from small and local businesses. Launching in 2020, OregonBuys could save the state as much as $1 billion over the next few years, doing away with the outdated manual and paper-based systems used by dozens of separate state agencies to buy goods and services.

Powered by Periscope’s BuySpeed eProcurement system, the system will enable state agencies to identify cost-cutting opportunities in their sourcing strategies and compare purchasing across Oregon’s own contracts, those managed by other public sector organisations, cooperative contracts, and the open market.

DO: Nurture homegrown tech startups

It’s in a city’s best interest to create an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Entrepreneurship not only creates jobs, it drives innovation. Supporting tech startups keeps the homegrown talent at home and may even lead to disruptive innovation that could improve the lives of millions.

The Innovation Cities Index 2019 compared 500 cities to find the best places that nurture startups for new ideas to be brought to life.

New York City took out top honours for its commitment and investment to tech startups. The city’s tech sector has grown rapidly with an estimated 7,000 startups, including unicorn startups such as Peloton, Infor, Compass, Zocdoc, Sprinklr, SquareSpace and Warby Parker, in addition to some 100 incubators and accelerators, 200 co-working spaces and 120 universities.

The investment has clearly paid off. Today, the city’s entrepreneurial ecosystem is worth $71 billion.

Tokyo was recognised as the world’s second best innovation hub for its robotics research and development and 3D manufacturing technology, while London’s thriving tech sector has created a hub for many of the tech industry’s big players, such as Facebook, Apple, Intel and Google.

Nurturing startups is also vital to drive the green economy and could lead to the next big thing, like the Bill Gates-backed Heliogen, a startup that aims to turn solar power into fuel.

DON’T: Overlook smaller and developing cities

People are drawn to cities for work and opportunities, so it’s hardly surprising that the world’s leading innovation hubs like New York, London, Singapore and Paris are large metropolises with millions of inhabitants.

However it is often the smaller cities, defined as those with less than 500,000 inhabitants, that have a greater need for innovation.

For one, most people live in these cities.

Furthermore, while smaller cities might have more difficulty sourcing public funds and attracting talent, smaller, fast-growing cities often pioneer best practices. With less bureaucracy, they are also able to implement innovation much faster.

There are more reasons why federal governments should do more to attract the high-tech innovation sector away from superstar cities to midsize cities, according to a Brookings Institute report, which links the negative effects of excessive tech concentration in large cities to factors such as “spiraling home prices and traffic gridlock” and “thinner talent reservoirs”.

DO: Make protecting data a priority

With drones, smart utility meters, wireless networks and surveillance cameras among the myriad ways urban infrastructure collects citizens’ data, cities have an obligation to build and maintain the public’s trust.

Outcry over the way infrastructure would collect and distribute citizens' personal data led Sidewalk Labs, the urban innovation arm of Alphabet, to scale back ambitious plans to create a futuristic smart city along Toronto’s waterfront. “The data may get used for public good,” said Mike Cook, president of Ontario-based cyber firm Identos. “But what else will it be used for and where does the citizen’s ‘rights’ start and end?”

Cities shouldn’t pull the plug on integrating technology in urban development, which in most cases, can vastly improve energy efficiency, traffic management and happiness. But technology in urban innovation shouldn’t come at the cost of personal privacy.

To mitigate the risks, the City of Toronto has launched public consultations to develop rules and regulations that govern privacy, data collection and digital infrastructure in smart-technology projects.

Other global cities are banding together to protect citizens’ digital human rights. In 2018, the Cities for Digital Rights initiative was launched by the three major cities of Barcelona, Amsterdam, and New York City with the support of the United Nations Human Settlements Program.

For Barcelona, which has a manifesto detailing its commitment to citizen privacy and data protection, privacy and compliance with the recent EU General Data Protection Regulation are at the heart of its data management and digital service design. The city’s DECODE project provides tools that put individuals in control of whether they keep their personal data private or share it for the public good.

DO: Collaborate with other cities

“Sometimes when you innovate, you make mistakes. It is best to admit them quickly, and get on with improving your other innovations.”

Cities can learn a thing or two from the late Apple cofounder Steve Jobs – but they can also queue-jump the learning process by learning from each other’s mistakes.

More than ever before, cities around the world are connecting with each other, sharing their experiences, successes and failures, and collaborating to find solutions and take real action to improve the lives of citizens.

By joining forces internationally, cities can drive progress faster and more efficiently. C40 is one example of a collaborative intiative that provides a networking opportunity for the world’s megacities to share knowledge and drive meaningful, measurable and sustainable action on climate change.

Through C40 networks, city practitioners from around the world advise and learn from one another about the successes and challenges of implementing climate action. More than 70% of C40 cities have gone on to implement new, better or faster climate actions as a result of participation, ranging from improved air quality to mass transit and building efficiency.

The EU’s International Urban Cooperation (IUC) programme is another knowledge-exchange platform that pairs cities and encourages city-to-city collaboration on communal issues, such as finding renewable sources of energy or addressing urban poverty.

Some recent IUC pairings include the cities of São Paulo and Milan, which teamed up to collaborate on safe, inclusive urban development, innovation and competitiveness.

Another knowledge-exchange pairing between Barcelona and New York City aims to provide the Spanish city with technical assistance to create an affordable housing strategy.

Joint procurement is yet another way for cities to collaborate. Smaller cities can join forces to receive better funding, lower the cost of procurement, arrive at scale and improve the degree of interoperability.